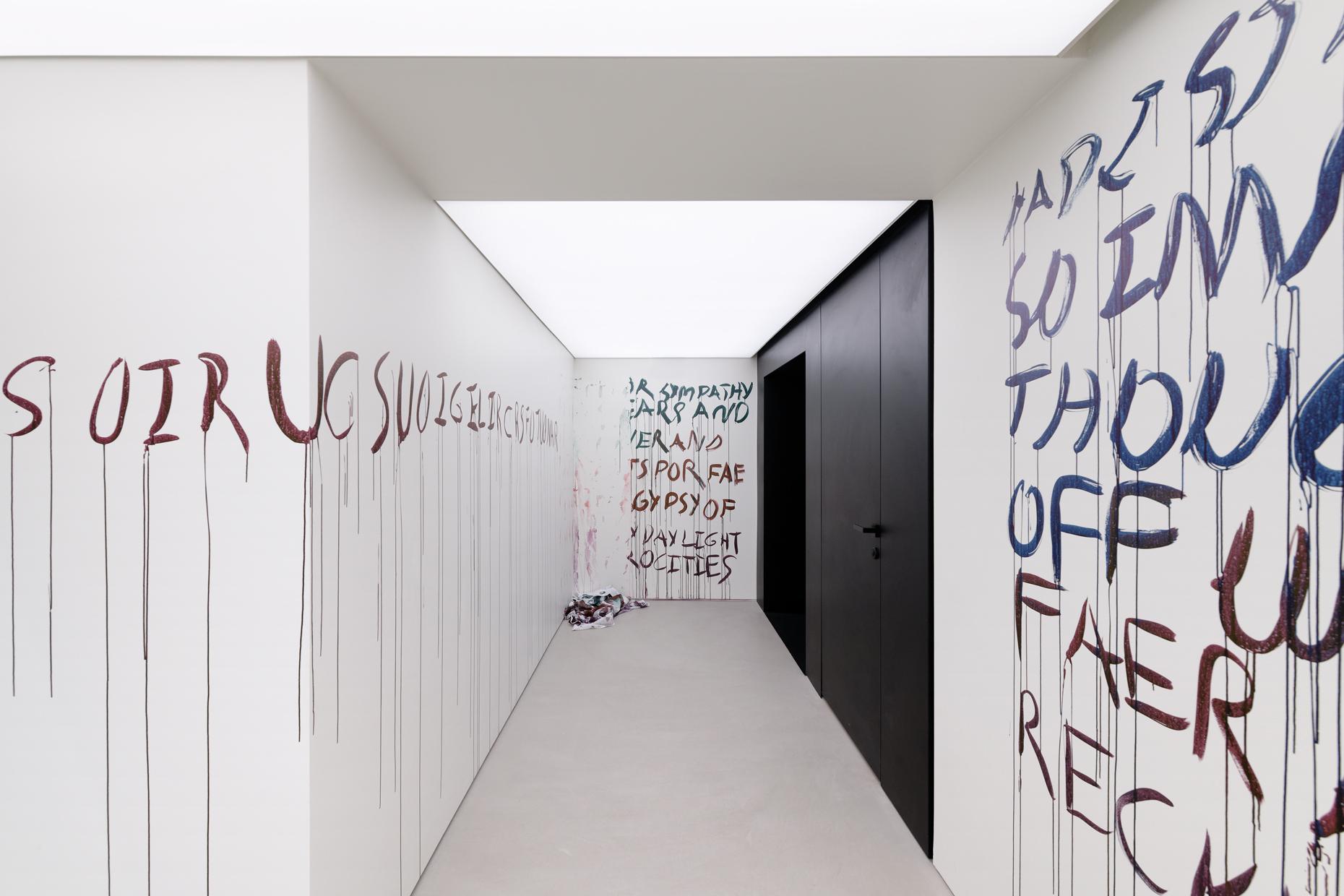

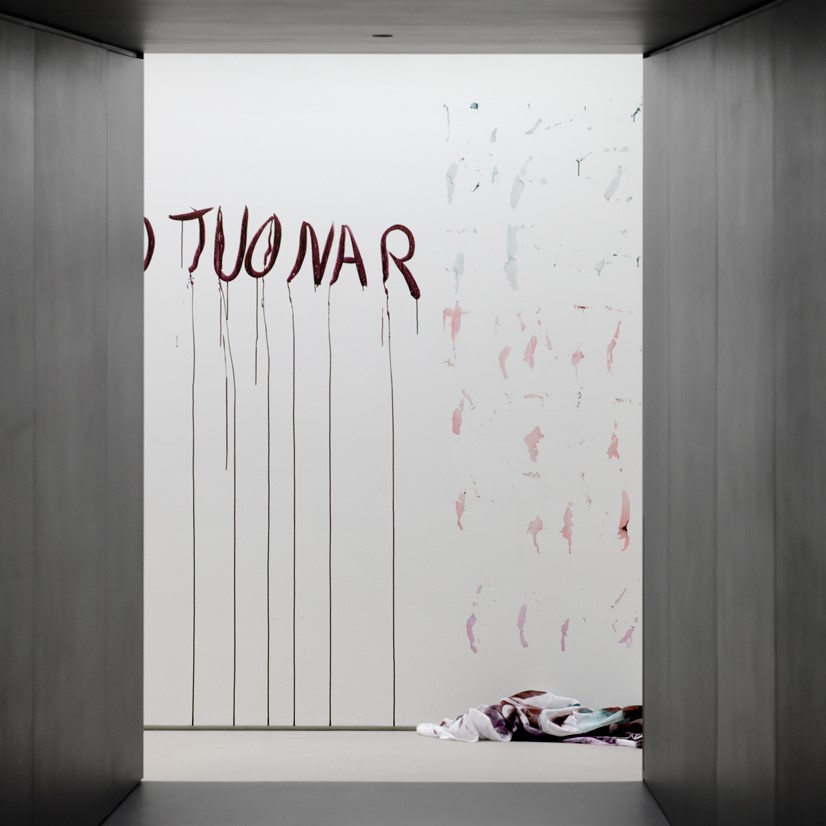

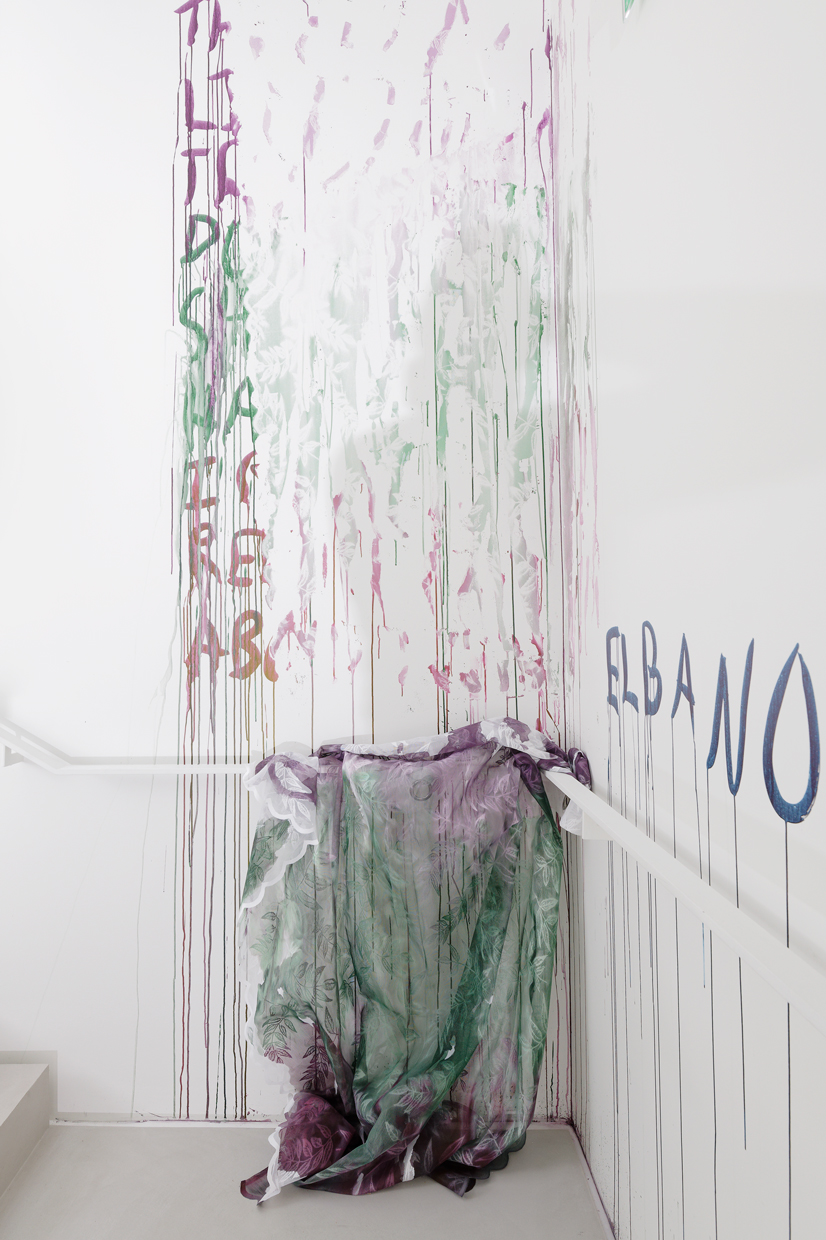

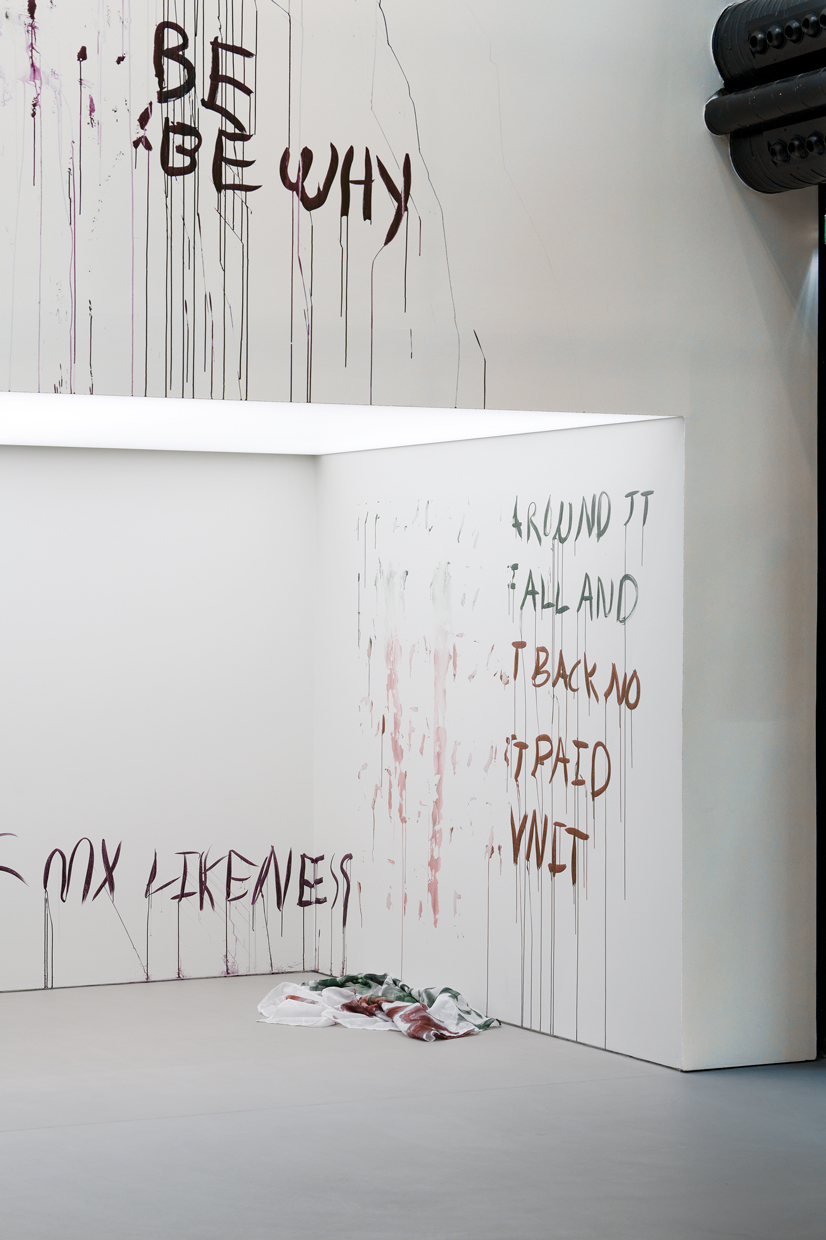

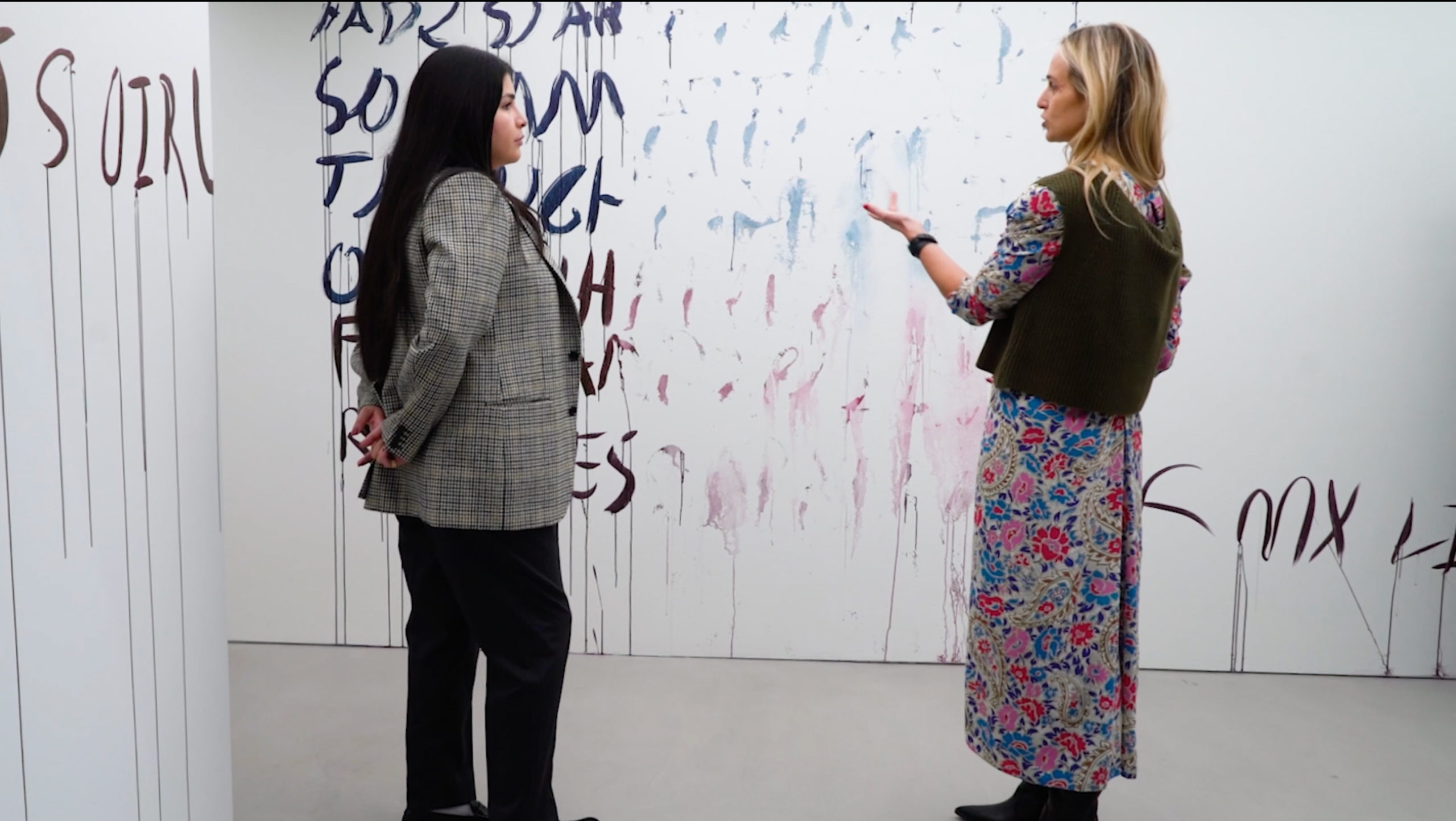

Ser Serpas, laureate of the Reiffers Art Initiatives Prize 2023

Ser Serpas was born in 1995 in Los Angeles. She is a graduate of HEAD Geneva and Columbia University in New York, she lives and works in Paris. Her artistic practice combines sculpture, poetry, painting and sound to create transversal compositions that resist simple categorisation in the face of fossilisation. She is represented by the Balice Hertling gallery in Paris and the Karma International gallery in Zurich. Ser Serpas is the 2023 Laureate of the Reiffers Art Initiatives Prize. L’artiste expose lors de la première exposition de la collection permanente de Reiffers Art Initiatives, « Les Apparitions ».

Biography

Texts

"Turning Trash Into Poetry Ser Serpas, a young artist known for kinetic arrangements of discarded furniture, opens up about her expressive way of processing the used world" by By Travis Diehl

— The New York Times, 2023

Serpas belongs to a loose cohort of millennial artists and poets, including Hannah Black, Precious Okoyomon and Rindon Johnson, rethinking found materials through deceptively deadpan sculptures. Like many of her peers, she favors objects that bear the marks of use, as if, having inherited a sorely used world, she’s making stanzas from its leftovers.

One blustery afternoon last November, I trailed Serpas and Rafik Greiss, her collaborator and gallery-mate at Balice Hertling there, as they hunted for inspiration in the 19th Arrondissement. Serpas was in Paris for a residency, relatively fresh from Tbilisi, Georgia; and Geneva before that.

“People tape things up here,” she said. “It makes it into a new object. Like these poles.” Right on cue, the city provided four metal rods loosely bundled with duct tape. Serpas moved in. She wove the rods through a wooden shipping pallet, and wedged up the contraption with a broken oscillating fan. Then she struck a pose herself, long hair wafting, electric-blue workwear and Day-Glo gloves popping against the wispy sky, while Greiss crouched and snapped her camera like a fashion hound.

Serpas usually works alone, and indoors, but this series is different. More narrative, she says, and more about her. The photos she and Greiss made are destined for her exhibition Jan. 25 through April 23, at the Swiss Institute in Manhattan, her largest institutional solo effort to date. The photos offer a peek at her process. The sculptures they depict lasted only minutes.

A culture’s refuse says a lot. The trash in Switzerland, where Serpas earned her M.F.A., is scarcer and better maintained. You need to know the garbage routes. In New York, the trash is plentiful, unruly, almost a point of pride. The sculptures are also self-portraits, reflecting the artist’s sensibility and spirit. In Paris, we came across a polite lineup of broken-up furniture against a hunter green fence. Serpas slotted the top of a captain’s table into a mirrored medicine cabinet. “Oh,” she said, “this makes a good tongue.”

In early interviews, Serpas often mentioned her teenage activism. “I don’t believe in art as activism, like, at all,” she told me. She moved to Morningside Heights in 2013 to pursue urban studies at Columbia. In New York, though, classmates who’d attended elite private schools in New England talked down to her about gentrification in Los Angeles. She drifted away from the dissonance of collegiate politics and toward the blurry, permissive worlds of art, fashion and nightlife".